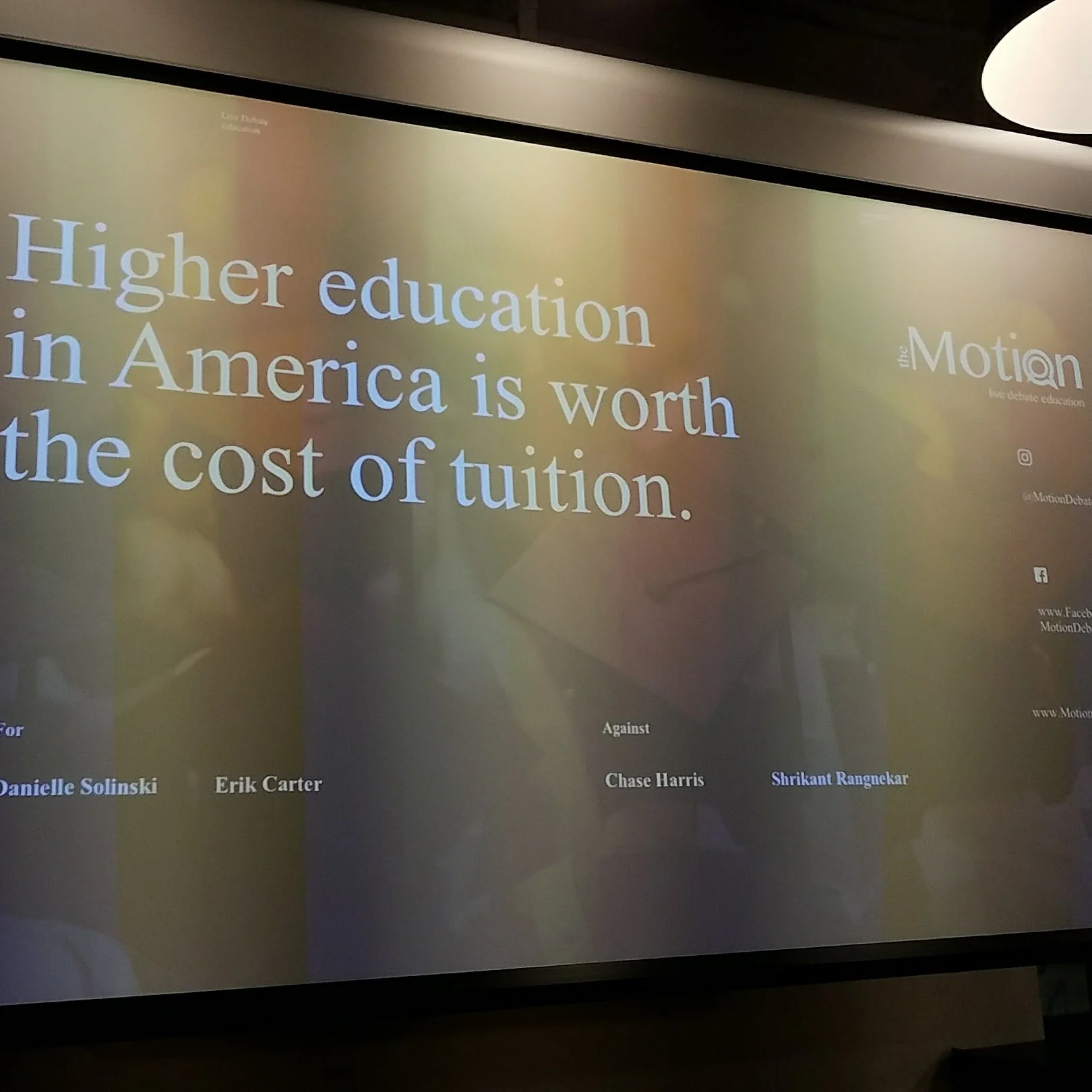

I am slowly figuring out how to get a pretty good sound quality out of these recordings. This one might be the best one yet. This debate was also pretty good, here are some thoughts about it in general.

At the start of the debate I spoke for a little bit about the idea of how to approach coming up with things to say. The Ancients called this inventio or “invention” – the creative act of coming up with arguments. It’s a great place to start in debate instruction as it reminds us that for thousands of years people thought of debating and arguing as a creative act, as opposed to a truth-seeking act, an act of transmission of fact, an act that distinguishes lies from reality, or any other such metaphor we have given to it in the Enlightenment hangover.

This debate started strong with a dynamic speaker who chose to deliver his remarks extemporaneously. He spent a few key moments on framing, a very important move to make in any debate, where you establish the limits of the debate. Framing is often phrased toward the audience as their charge or their role – what is it that they are meant to decide?

The short speech times mean that debaters cannot spend a lot of time on things other than developing their major arguments. This is not a disadvantage to the form at all; in fact, debates are always extremely time-constrained. Speakers must learn surgical precision in any persuasive situation as time is considered to be of ultimate value.

The debate focused a lot around the economics and pay off of a college degree. I wondered about this approach – of course, it’s the easiest way to make sense to the audience, but there are a number of other approaches that the debaters could have taken on the question of the opposite “how can you not afford it?” – as well as university as the driving force for research, innovation, and things like that. Centering the debate here would also be pretty interesting as there’s a lot to consider.

The first two speakers spoke about economics more than the second two, but I would suggest that perhaps the second speakers should dismiss the economic concerns (“That has been covered, let’s dive deeper”) and engage a lot more with their arguments about the nature of learning, the type of learning that is valuable, and the price we pay when we misconstrue a sticker price for a personal value. Both speakers had a lot of great things to say, and a very attractive and personal style.

What I really liked about this debate was the extensive use of narrative, or storytelling, to frame and advance arguments. This is very difficult to do. It requires a lot of confidence, but more importantly, familiarity with your information to a point where you can weave it into a story.

There’s a big difference between telling an audience “34% of graduates never use their degree skills” and “What happens when you attend a university? First, you pay a massive amount of money, then you interact only with people who are not innovators or they just don’t know much, you delay your working life, and at the end of it you decide to do something else with your life.” This is much tougher than it appears, and I’m sort of inspired after the debate last night to write up some lessons that might help students reach this level of speaking. People at the start of a persuasive speaking practice seem to want to make lists and read off data as if the audience was a machine meant to process it. I call this “jukebox” or “vending machine” audience theory after Ralph Ellison’s brilliant essay on how to interact with American audiences. No chance of that in last night’s debate. Everyone was quite good at framing and narrating their arguments.

It was also a pretty relaxed performance as well, which communicated to the audience that the stakes were important, but there was no fever-pitch, “all or nothing” rhetoric from either side. Firm positions were established, and questioned. And that’s a pretty good debate. Of course, like any debate, the clash – those points of disagreement that the audience needs as a guide for a decision – were not as well formed as the debaters could have done – but in the end it didn’t matter much. Audience questions were good – the one audience member asking about the stakeholder of the American society comes to mind. I think the audience was eager to hear more than arguments about cost and return in one’s career.

If the debate were approached with the assumption that career is a 20th century conception and that most people learn job skills while working with and among other professionals, what is university then? The debate could take the turn of imagining another university, one that puts its obligation toward thought and social interaction with those you wouldn’t choose to socialize with first and provides you some job help but doesn’t make it the centerpiece of your time there.

The debate was quite good – have a listen. Every speaker did well in making the point they were trying to advance. Great distinction in style as well – things like word choice and sentence construction were effective and engaging.

Clash is a difficult thing to master in debate. I think it has to be the hardest thing and the thing that makes debating unique when compared with other modes of communicative decision-making such as discussion, argument, or persuasive monologue. The importance of clash is the importance of a GPS in a strange city: Where do you want to go? Turn here, exit here. You’ve arrived at your destination. But perhaps it’s more than this – perhaps it’s like a concierge service along with a GPS: Ready for dinner? You simply must eat here. It’s the best in town. Now, turn here, exit here. Bon Appetit!

There’s not a lot written on clash – which is strange to think about given its importance in helping audiences decide. But the history of debate education in the US really hasn’t been about helping audiences decide. It has been more about how to configure the audience into a perfect sounding board for the good arguments we make elsewhere. Interactivity as a source of good argumentation between speaker and audience has never been a focus. Look to the guidelines for the World Championship for a stunning example of how removed it is. Perhaps this growing debate education movement in New York could be about re-discovering audience via Aristotle, Cicero, Quintilian, and others, and making more than a picture frame from the crowd. How about a co-conspirator? That’s my goal. This requires trusting your audience, which everything in our society tells us is a bad idea. We have to distinguish doxa from episteme. Not to say one is better, but to say one is different. How we do that remains to be seen.